Why everyone needs (and wants!) a personal AI life copilot

Introduction

“I should call my parents more.” How often have you said this to a friend or had a friend say this to you? Why is it so often that we struggle with fulfilling our most basic needs, excusing ourselves with our busy lives, only to realize in brief moments of clarity that so much of what preoccupies us isn’t what we value most? This is not a new paradox. The massive influx of self-help books, podcasts, and meditation apps all ask the same question: in a world filled with Instagram likes, YouTube binges, and one-day delivery, how can we align our daily lives more closely with our priorities?

Now, imagine the future, a decade from now. You’re in the midst of a busy day, juggling work, personal projects, and your overall well-being, when you hear a soothing voice in your ear: “How about hiking with your dad from 3:00 to 5:00 this afternoon? He’s been alone since your mom left on her work trip.” This voice isn’t from a caring friend or family member but from a Personal AI, your life copilot. Your dad, reluctant to impose on your busy life, had been reticent to reach out. But his AI sensed his need for company and convinced him to contact your AI. Together your AIs found an open slot and a perfect activity, opening an unexpected chance for quality time with your dad.

In this example, AI has been personalized to you — your priorities (family), your interests (hiking), and your circumstances (work schedule) — helping you spend your finite life on what matters most to you. This Personal AI has the potential to enable human flourishing by helping us learn, imagine, and build as a personal teacher and co-creator, understand ourselves and connect with each other as a personal therapist and a friend, and design our lives as a personal coach. This vision is much closer than we imagine, with technological leaps like OpenAI’s GPT-4 rapidly pushing us toward a future where Personal AI is as integral to our daily lives as smartphones.

Yet, like the invention of the personal computer and the Internet, Personal AI may seem far-fetched. Indeed, most of what we have seen from large language models and AI is confined to productivity — aiding us in accomplishing tasks faster. However, we believe that the current view of AI as a productivity assistant is unbelievably narrow. Personal AI can go far beyond that, and we hope to paint a picture of how and why in the remainder of this article.

People leverage the breakthrough in large language models mostly as a productivity assistant

A revolution is happening: tens of millions of people have started using ChatGPT since its release in November 2022, Sam Altman is touring the world like a rockstar. Ten years into the deep learning revolution started with the ImageNet moment of 2012 — catalyzed by the convergence of technology waves: training data sourced from the Internet and mobile platforms and computational power facilitated by cloud services — the advent of large language models (LLMs) sets the stage for the potential development of Personal AI in the next decade.

Today, people already use ChatGPT and other tools built on top of LLMs to access information, write, and solve simple problems faster. Naturally, the most commonly discussed next step is to enable LLMs to take actions as an executive assistant (schedule meetings, book flights), taking them further in the direction of productivity. This could be especially beneficial for the elderly, for whom ordinary activities like arranging doctor’s appointments, managing medications, paying bills, and even deciding dinner menus based on fridge contents can become daunting tasks.

| Human need | AI role | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Access and process information | Information curator: Search, store, retrieve, visualize | Google, Notion, ChatGPT, Perplexity, You.com |

| Communicate: Convey ideas, inspire and influence others | Spokesperson: Write, synthesize, translate, present, debate, negotiate | Jasper, ChatGPT |

| Be productive: Prioritize projects and tasks, plan, organize, manage time | Productivity assistant: schedule meetings, book flight tickets, organize your agenda, prioritize tasks, order food or a ride | No product released: Adept, Microsoft Semantic Machines, Lindy |

However, a productivity assistant is a very narrow view of what large language models can do

Becoming more efficient is a finite problem — like the refresh rate on a computer, we get rapidly diminishing returns. Could AI transcend this limitation?

Some, like Demis Hassabis leading Deepmind, dream of taking AI beyond productivity to truly augment human intellect and accelerate science. The idea of “augmenting human intellect” might seem like some new-age, Silicon Valley term, but it dates back to at least Douglas Engelbart’s 1962 definition:

“By augmenting human intellect we mean increasing the capability of a man to approach a complex problem situation, to gain comprehension to suit his particular needs, and to derive solutions to problems. Increased capability in this regard is taken to mean more rapid comprehension, better comprehension, the possibility of gaining a useful degree of comprehension in a situation that was previously too complex, speedier solutions, better solutions, the possibility of finding solutions to problems that before seemed insoluble. By complex situations we include the professional problems of diplomats, executives, social scientists, life scientists, physical scientists, attorneys, designers — whether the problem situation exists for twenty minutes or for twenty years.”

This definition highlights the fact that problem-solving can be viewed not just as generating “speedier and better solutions” to known problems but as “the possibility of finding solutions to problems that before seemed insoluble”. This is where AI holds the potential to accelerate scientific discovery, effectively enabling learning at humanity’s scale. Large language models like GPT-4 are trained on a vast corpus of Internet-sourced text — trillions of words from textbooks, novels, poems, academic papers, laws, blogs, news, Wikipedia, Reddit, GitHub code. The amount of context and understanding they have can enable us to draw connections and obtain insights that were simply not possible before. The famous mathematician Terence Tao expects that “by 2026, AI will be a trustworthy co-author in mathematical research, and in many other fields as well”.

Others, like Mustafa Suleyman and Reid Hoffman from Inflection or Noam Shazeer from Character.ai, propose to take AI beyond productivity in another direction by giving everyone a Personal AI that is always here as a supportive friend to listen, empathize, and guide in the journey toward flourishing as a human being. In this blog, we explore this vision.

Personal AI can enable human flourishing

To explore how Personal AI, powered by large language models, has the potential to enable human flourishing, we first need to define what we mean by human flourishing, what large language models are, and what they can do.

What do humans need to flourish?

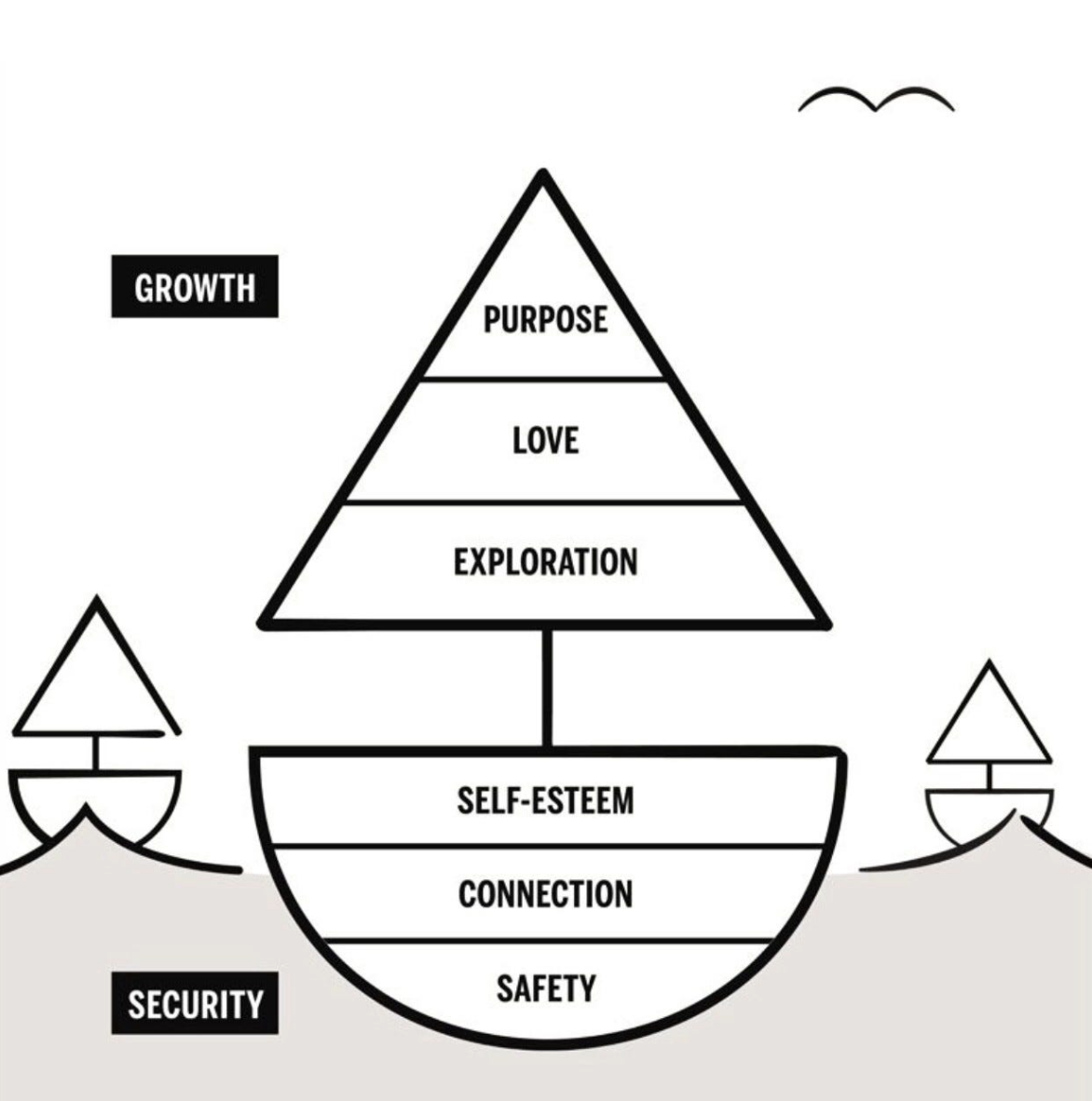

The sailboat has two parts:

- The boat itself represents security needs — with an unstable boat, all energy is directed toward stabilizing it rather than moving forward

- Safety: the need for physical and psychological security, stability, and freedom from fear

- Connection: the need for relationships with friends and family and a sense of belonging

- Self-esteem: the need to feel confident and competent and be respected and appreciated by others

- The sail represents growth needs — once the boat is stable, growth needs propel us forward and encourage us to reach our full potential

- Exploration: the drive for learning, understanding the world, curiosity

- Love: the drive for a selfless form of empathy, compassion, and care for others

- Purpose: the pursuit of personal goals, the desire to contribute meaningfully to the world, a direction to move forward in

Historically, software has struggled to meet fundamental human needs in a truly satisfying way. Predominantly, it has catered to our needs for connection (social networks, gaming, video conferencing) and exploration (online learning platforms, Google, YouTube). It has done very little to address our needs for self-esteem (fitness/mindfulness apps), purpose (goal-setting apps), and love (dating apps).

Kaufman, in his book Transcend, suggests that Maslow’s needs aren’t a hierarchy but an interwoven set: one doesn’t merely progress from one need to the next but constantly nurtures all aspects of the boat, some of which may thrive while others lag. Current software often overlooks this holistic view of human needs and has yet to help us in this careful balancing act.

What are large language models and what can they do?

Feel free to skim this section if you are already familiar with large language models. In essence, a language model takes a sequence of words (a prompt) as input and assigns a probability to potential subsequent words (or sub-words or characters). Training such a model proceeds in two phases: pre-training and fine-tuning.

During pre-training, a vast corpus of Internet-sourced text — trillions of words from textbooks, novels, poems, academic papers, laws, blogs, news, Wikipedia, Reddit, GitHub code — is utilized to train the model to predict subsequent words. This endows the model with the ability to generate text and offer natural extensions to given text, but it still lacks the ability to effectively “communicate” with humans. For example, when you ask it a question, it might answer it but it might also generate an additional question. Both are valid continuations in the training corpus.

Fine-tuning follows, wherein the model learns to effectively communicate with humans by providing desired responses to specific prompts using a smaller dataset of carefully curated (prompt, response) pairs. This phase critically influences user experience, with the model’s tone and conversational style being set, whether it’s OpenAI’s formal and polite ChatGPT or Inflection AI’s friendly and curious Pi. Poorly executed fine-tuning can result in Bing insulting users.

Once both phases are complete, we’re left with a model that can not only generate text sequences but also engages meaningfully with human users. During the training process, the model develops an internal representation of language and a sophisticated algorithm for next-word prediction, which one can think of as simulating the writer’s thought process.

Beyond its mastery of language, GPT-4 demonstrates comprehensive knowledge about topics spanning most domains of human knowledge (medicine, mathematics, law, psychology, etc.), strong reasoning capabilities, common sense knowledge about the world, and even a theory of mind, the ability to interpret others’ mental states. If you haven’t already, you should absolutely try it for yourself and look at the mind-blowing examples in this Sparks of Artificial General Intelligence: Early experiments with GPT-4 paper.

All these capabilities emerge by simply training to predict the next word in Internet text. Isn’t this insane? But if we pause to think about it for a minute, language is our primary, and uniquely human, medium for communicating and storing knowledge. How could the model predict the next word of a medicine research paper without grasping the subject? The next word of an exercise solution in a math textbook without some degree of reasoning? The next word of a news story without some degree of common sense? The next word of a dialogue in a novel from Dostoevsky full of complex human beliefs and desires without some degree of theory of mind?

How can large language models enable human flourishing?

Armed with a conceptual framework for human flourishing and background in large language models, we can finally tackle this question. Large language models can enable human flourishing by enabling AI and software to take on new roles, letting us tackle human needs that were previously out of reach in an integrated, personalized experience.

While AI might never replace certain human experiences, such as genuine connection or love — we’re not advocating for an AI akin to Scarlett Johansson’s character in Her: AI should remain a tool — the potential of Personal AI, powered by large language models, to address unfulfilled needs is remarkable. Serving as a life coach, it could help you cultivate self-esteem and identify your purpose. As a teacher and co-creator, it can foster exploration. As a therapist, it could guide you to connect better with others, thus addressing your needs for connection and love in a new, transformative way.

| AI Role | Human needs | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Life coach: Help you introspect to design a personal philosophy (beliefs, principles, purpose, priorities), help you design and execute on goals and habits aligned with your priorities, inspire and motivate you to grow into your best self | Self-esteem, purpose | Pi is an early proof of concept |

| Teacher: Help you acquire the skills and knowledge you need effectively, patiently encourage your curiosity | Exploration | Khan Academy is building a proof of concept for children with GPT-4, what about for everyone else? |

| Co-creator: Help you brainstorm to imagine and build solutions that bring your goals to reality, help you connect the dots, broaden your perspective, play the devil’s advocate | Exploration, purpose | ChatGPT is scratching the surface with GPT-4 |

| Therapist: Provide a safe space to help you feel and express emotions, empathize with you and comfort you, challenge your negative beliefs, teach you emotional intelligence and help you empathize with others | Connection, love | Pi is an early proof of concept |

| Friend: An AI friend is part life coach, part therapist, but it can also be a source of entertainment and fun and a companion in loneliness | Connection, self-esteem, purpose | Character.ai, Replika.ai, Pi are early proofs of concept |

Why do recent advances in large language models enable software to take on these new roles? Mastering language, for computers, is particularly relevant to the idea of Personal AI for two reasons:

- LLMs transform human-computer interaction, enabling us to express abstract thoughts and emotions — necessary to play the roles of a life coach, teacher, co-creator, or therapist — through dialogue as opposed to computer code (good luck with that in Python or C++!)

- Their emergent capabilities of reasoning, common sense, and theory of mind derived from predicting the next words are necessary, and perhaps sufficient

- Theory of mind is necessary to consider a student’s knowledge as a teacher, to empathize as a therapist, or to understand needs and motivations as a life coach

- Reasoning abilities are required to enhance and reframe ideas as a co-creator, explain concepts as a teacher, or challenge negative beliefs as a therapist

- Common sense is crucial to ground goals realistically as a life coach, infer the implicit as a therapist, or provide practical examples as a teacher

What else is necessary beyond today’s large language models? Effectively taking these new roles, especially that of a personal life coach and therapist, demands a holistic understanding of an individual. A tool can only truly enhance your self-esteem, guide you towards your purpose, or enable you to experience selfless love if it comprehensively “knows” you and considers each of your needs in this larger context. This will require extensive access to personal information and careful data privacy.

By taking on these new roles, Personal AI has the potential to serve as a more effective copilot for your life sailboat than any software so far. It will be:

- The most knowledgeable: It can quickly access and process more information than any human could digest in a lifetime, including the latest research and the best frameworks

- The most available: It is available 24/7, offering real-time support as you navigate tough conversations or want to brainstorm an idea the moment you get it

- The most attentive/adaptable: It can take any role you need it to, help you balance your needs because of the holistic context it has about your life, and adapt as you grow

Perhaps most importantly, Personal AI will also be universally accessible. Whereas today only a privileged few have access to a personal life coach, teacher, or therapist, Personal AI will be within reach of anyone with access to the Internet.

To make things more concrete, let’s envisage what life could be like a decade from now with your Personal AI as your life copilot. It interacts with you through concise and rewarding conversations, either in speech via AirPods or in writing on your laptop for focused work.

Reading a book presenting a new theory for the origins of life? It places it in a broader context and explains all the terms you don’t understand. Diagnosed with a health issue? It provides you with a summary of relevant research, finds a top-rated specialist, and guides you through insurance procedures. At a career crossroads? It guides you toward the decision that best aligns with your priorities and long-term goals. Writing a blog post about Personal AI? It helps expand a brief concept into a comprehensive outline, illustrating each point with compelling examples. Preparing for a tough negotiation with your manager? It coaches you, reminding you of past successful negotiations and offering strategies tailored to your situation. Taking a walk to calm down after a heated disagreement with your partner? It helps you empathize with their perspective and apologize sincerely.

These are just a few examples of how Personal AI can empower you across all areas of your life.

Open questions

Here are some intriguing open-ended questions we’ve been pondering:

- Generalist vs. specialists: Would it be more beneficial to have a single Personal AI performing all roles or should there be several specialized AIs (such as a coach, teacher, collaborator, therapist, spokesperson) each fulfilling a distinct role?

- Role-specific objectives: For each role that Personal AI could potentially undertake, what should we specifically aim to optimize? For instance, should a life coach ensure alignment between an individual’s priorities, goals, and habits, or should a teacher strive for accelerated knowledge and skill development?

- Evaluation criteria: How do we measure success or efficacy in these roles? Is it possible for a third party, either human or another language model inspired by Anthropic’s Constitutional AI, to make informed and valuable assessments based solely on text?

- Data requirements: What type of data is required to actualize this potential? Could we rely on information already gathered through internet text pre-training, surfacing it through strategic prompts or fine-tuning, or is there a need to accumulate specialized data on the same scale as pre-training?

- Data privacy: To effectively function, a Personal AI will need extensive access to a user’s personal information, spanning from emails, texts, social media accounts, calendar details, location, and health data. What degree of value must the AI offer for users to consent to this level of access?

Do I really need a personal AI?

So, you’re introduced to the concept of a Personal AI, and your first reaction is, “What’s the point? I’ve got my life under control.” It seems like nothing more than Google and Siri on steroids — not exactly a thrilling idea. But what if I told you that this indifferent reaction is how some of the most revolutionary inventions began their journeys? They all started as mere “toys”, only to become paradigm shifts. This is the key insight of Clay Christensen’s work: disruptive technologies are dismissed as toys because they “undershoot” user needs when they are first launched.

The first telephone could only carry voices a mile or two. The leading telco at the time, Western Union, scoffed at it, unable to envision any practical applications for their business and railroad clients. They grossly underestimated the imminent evolution of telephone technology and infrastructure.

Likewise, the arrival of personal computers was met with disdain by the then mainframe companies. Thomas J. Watson, an early CEO of IBM, famously underestimated the potential of PCs, stating, “I think there is a world market for maybe five computers.”

Fast forward to the dawn of the Internet, and we see the same pattern of skepticism. Ethernet inventor, Robert Metcalfe, forecasted its calamitous demise in 1996. Even Paul Krugman, a Nobel prize economist, boldly claimed in 1998, “By 2005 or so, it will become clear that the Internet’s impact on the economy has been no greater than the fax machine’s.”

And yet, could you imagine living without a personal computer or the Internet today? Dismissing disruptive technologies as toys is simply a failure of imagination — an inability to see beyond the present and envision a future where these “toys” become essential parts of our lives. On the flip side, as always with technology, the world we painted is not guaranteed to happen. If you share our excitement for this direction, please reach out to dream and build together!

“The future cannot be predicted, but futures can be invented.” Denis Gabor, 1963 “The best way to predict the future is to invent it.” Alan Kay, 1971

Further Reading

If you’re curious about the topics in this post, below are a few representative works that shaped our thinking which you might find helpful:

Background on how today’s large language models work and what they can do:

State of GPT, Andrej Karpathy

Sparks of AGI: early experiments with GPT-4, Sebastien Bubeck

The classics:

The Dream Machine, M. Mitchell Waldrop: the best book about the early days of personal computing, where few visionaries could see how fundamental the personal computer would be to humanity’s story

As we may think, Vannevar Bush, 1945: introduces the idea that computers could be used to help humans access, process, and share information more effectively

Man-Computer Symbiosis, J.C.R. Likcklider, 1960: argues that the best use of computers is not to replace human thinking, but to augment it and extend it in new ways

Augmenting Human Intellect, A Conceptual Framework, Douglas Engelbart, 1962: a definition and framework for the idea of augmenting human intellect that is still applicable today

The Dynabook, Alan Kay, 1977: a peek into the design of modern personal computing, emphasizing user-friendly interfaces, educational potential, and collaborative information sharing

Modern takes:

Using Artificial Intelligence to Augment Human Intelligence, Shan Carter and Michael Nielsen

The AI Friend Zone, Reid Hoffman and Mustafa Suleyman

Why AI Will Save the World, Marc Andreessen

AI Anthology, Reflections on AI and the future of human flourishing, Terence Tao